Extinction of ancient languages of tribes and other small linguistic communities is a common scenario in contemporary India, a country of hundreds of identifiable languages and thousands of dialects. This is particularly noticed in the Union Territories under direct central administration, where Hindi, emerged in the garrisons of the Moghals a few centuries ago, is now imposed as language of administration and education.

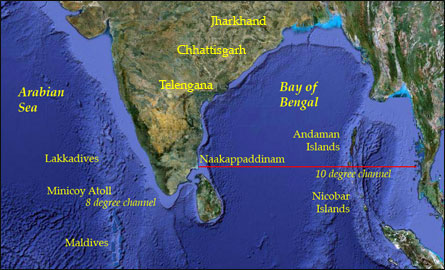

A typical example of the picture is Minicoy, the southern most atoll of the Lakkadives archipelago, a ‘protected territory’ where India is maintaining a naval base to guard the Eight Degree Channel of the Arabian Sea.

Minicoy, which was culturally and historically a part of Maldives, loses its unique language Mahl (Maldivian or Dhivehi) to Hindi and Malayalam, as it is kept away from cultural contacts with Maldives. People of Minicoy struggle to retain the language by depending on Maldivian radio and television.

But many tribes in central and eastern India are not as fortunate as the people of Minicoy.

Citing the number and variety of tribal languages involved, and the absence of written script for them, Hindi makes easy inroads into the administration and education of the newly created tribal states such as Jharkand and Chhattisgarh.

Political observers point out that a hidden agenda behind the demarcation of these states was avoiding the carving out of a state for the deserving Chandelas, the largest of the tribes, as it would mean recognising their language as one of the major languages of India. The scheme is that tribal languages have to be replaced by Hindi. A considerable number of the tribal languages of these states are Dravidian.

Telengana will soon join the list, making a north-south column along with the tribal states, weakening the concept of linguistic states and opening the tribal belt for Centre’s economic and linguistic agenda, political observers said. It is not without reason the Centre readily agreed for Telengana, especially when it is fighting a war now for grabbing the land of the tribes, observers said citing media reports that recognition for Telengana was actually 'conspired' by M K Narayanan.

Today’s Indian Establishment has scant respect for Nehru’s grand idea of protecting every strain of the variety of cultural and linguistic heritage, particularly of the endangered tribes of India. No wonder, people from some of the northeast frontier states of India shun Hindi films and music as taboo.

In colonizing the Andaman Islands in 1858, the first Indians taken by the British were prisoners. For a long time Port Blair the capital of the archipelago remained a dreaded place for incarcerating freedom fighters of India.

The native tribes of the archipelago, some of them cannibals, were either killed or died of diseases brought by the colonizers.

“Having failed to ‘pacify’ the tribes through violence, the British tried to ‘civilize’ them by capturing many and keeping them in an ‘Andaman Home’. Of the 150 children born in the home, none lived beyond the age of two,” says Survival.

During the Second World War in 1942 the Japanese occupied the islands and handed them over to Subhas Chandra Bose as part of his Provisional Indian Government formed in Singapore.

The British regained them in 1945 and India inherited them in 1947.

Independent India was extremely careful in seeing the islands not monopolised by settlers of any particular ethnicity of geographical proximity from the sub-continent. Naakappaddinam in the Coromandal Coast is the nearest point to the Ten Degree Channel sea-route to the islands.

By bringing in motley of people, the ‘national interest’ of India and the official language status of Hindi were maintained. But this care was not taken in protecting, promoting and giving due status to the aborigine people or their languages.

The surviving tribes depend largely on the Indian government for food and shelter, and abuse of alcohol is rife, says Survival.

Boa Sr told Prof. Anvita Abbi, a linguist who studied her for many years that she felt the neighbouring Jarawa tribe, who have not been decimated, were lucky to live in their forest away from the settlers who now occupy much of the Islands.

“With the death of Boa Sr and the extinction of the Bo language, a unique part of human society is now just a memory. Boa’s loss is a bleak reminder that we must not allow this to happen to the other tribes of the Andaman Islands,” said Survival.

The archipelago of both the Andaman and Nicobar chain of islands were known to ancient Tamils by the name Nakka-vaaram islands.

Nakka-vaaram in old Tamil means ‘the hillside of the naked people.’

Nakka as adjective means naked (Nakkan: naked person, Pingkalam lexicon 5:169) and Vaaram is hillside (Dravidian Etymological Dictionary)

The early Tamil-Buddhist epic Ma’nimeakalai of c. 5th century CE that extensively deals with the maritime geographical knowledge and contacts of ancient Tamils, talks of a trader who was shipwrecked in the island of hills of Nakka-Chaara’nar (naked tribe), who were cannibals. The trader was spared and shown with generosity because of his knowledge of their language. He enlightened them to give up cannibalism and to become helpful to mariners. (Ma’nimeakalai 16: 10-125)

Ma'nimeakalai also equates Nakka-chaara'nar with Naakar, enlightening us on the affinities among the aborigines carried the identity Nagas in Sri Lanka, South India and Southeast Asia, who were probably people of Austro-Asiatic origins.

The Chola inscriptions of 11th century CE mention Maa-nakka-vaaram (the great Nakka-vaaram archipelago) as one of the territories conquered by Rajendra in his maritime expedition.

Several terms now obsolete in Tamil diction (Winslow), such as Nakkavaari (a person from Nakkavaaram and also a species of coconut palm), Nakkavaarak-kachchavadam (trade with Nakkavaram which is money for goods and in which one does not trust another), etc speak of the long contacts of Tamils with the archipelago of Andaman-Nicobar.

The Tamil name Nakka-vaaram survives today in the name for the southern part of the archipelago as Nicobar (just as Malai-vaaram becoming Malabar).

No comments:

Post a Comment